Do You Sleep?

Text and Photo © A Neikter Nilsson, JE Nilsson, CM Cordeiro 2013

Judging from the numerous books launched by Eurasian authors on their heritage and family history, it seems that the Eurasian community in Singapore has a general strong interest in research on genealogy, which in itself makes for interesting study due to a mixture of cultures, ethnicities and even traditions in cuisine.

The Portuguese with their sense of inherent adventure, had close ties to the East India trades already in the early 1600s. It is probably these factors in combination that landed the Cordero / Cordeiro family in East Asia in the first place. The genealogy of the Cordeiros can be traced from the highlands of Andalusia in Spain during the Medieval times, to the autonomous archipelago of the Azores of Portugal (ca. 1600ff), right through to Macau (ca. 1800ff) and then to Singapore during the early 1900s. To that extent, one could argue that the Cordeiros have flown flags of many colours, the most prominent (for the older generations of the family) being the vibrant colours of Portugal.

A more artistic rendition of the flag of Portugal, overlaid with the mathematical formulation of Le Chatelier’s principle, here metaphorically referring to that given time, an equilibrium of sorts will be reached in most situational contexts, considering both the migration of people and of the flux in global trade.

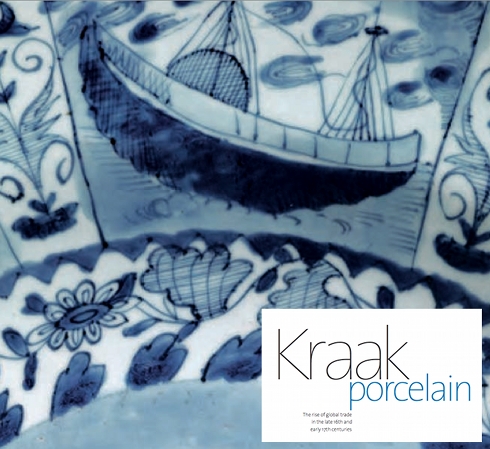

The Cordeiro family have their global trade roots in wine, having been wine merchants at one point or another in the family history. In connection with wine, food, dining and a certain lifestyle of the times, the Cordeiro family coat of arms was also recorded as one of the oldest in the world to be found on Chinese “Kraak” Export porcelain of the late 16th century:

“Some of the most important kraak ware pieces, and certainly the rarest group, are those decorated with armorials. The Portuguese were the first Europeans to bring kraak porcelain to Europe, followed by the Spanish and the Dutch. It is therefore natural that the very few armorial pieces of kraak porcelain known are mostly for the Portuguese market with the exception of a few for the Spanish. To date there are less than 30 recorded kraak pieces decorated with armorials or pseudo-armorials, mostly in the museum collections although a handful are still in private hands. These include the ones with the arms attributed to Dom João de Almeida, Cordero or Cordeiro family, Garcia Hurtado de Mendonza, Vilas-Boas and Faria or Vaz, D. Francisco de Mascarenhas, the Augustianian order and those with the pseudo-armorial of the hydra.” (Welsh 2004:14)

As with today when it is said that Italy plays no small role as a global economic source of influence, intriguing stories of adventure, mutiny and piracy in firsthand account of what happened to one set of such kraak cargo onboard the Portuguese ship São Tiago in 1602 can be found by Italian Florentine Merchant Francesco Carlettí in his Codex 1331 (T.3.22) preserved in the Biblioteca Angelica in Rome. A XVIIth Century Manuscript, known as Ragionamenti del mio viaggio intorno al mondo (modern print 1964), this book also describes the fantastic stories of a man who had tried to facilitate the exchange of goods between the Far East and Europe, and after 15 years spent circumnavigating the globe (the first ever of its kind documented) beginning from Cadíz Spain, he arrived home in Firenze with nothing except his manuscript.

In from the morning’s walk, wrapped snug when outdoors in a wool shawl made in Italy, which I sometimes have a Linus (of Peanuts) attachment to even in high summer. In Sweden, the seasonal transition between winter and spring is all but marked with, a change in footwear. From leather ankle boots, to canvas. A deceptively elementary and uncomplicated transition.

Noting that I was born on the island of Singapore just to move to settle on another island, albeit smaller, in the southern archipelago of the Swedish west coast that in itself is connected to the Swedish East India company – and now researching international business and world trade in my field of work – I begin to wonder if coming from a long line of seafarers, merchants and voyageurs, meant that I would often find myself drawn to the sea, surrounded by waters of some sort? Regardless of belief in any unavoidable destiny I can only establish that members of the family down to me, have been island hopping from Medieval times till today.

Currently, it is the shores skirting the surrounding waters of the North Sea of the Swedish west coast that I find myself delighting in, come these late winter days that are in transition towards the early Nordic spring, that is reflected in such different vibe in Carlettí’s (1964) stories of his voyages around the world.

A winter’s cove, Swedish west coast.

Colour Theory | Tea Leigh & Luke Reed.

Having been born in the equatorial tropics, I find it chilly outdoors despite the promise of a warming of temperatures at this time of the year. The cool temperatures hardly deter me though from taking unhurried late morning walks in quiet exploration along the small coves and bays that scallop these shores. Admittedly, I love the tranquil surroundings, where each step is accompanied by cold crisp air and the softest sounds of the crunch of frost lining on blades of grass under my feet.

Even if family history reveals an affinity for coastal regions, the Swedish west coast offers somewhat of a different reality to the equatorial beaches, not in the least because of climate or temperatures, but of colours and sounds.

Considering the boundaries between what can be known or not, there is only one short step to the most important contribution the Scandinavian countries have made to the world literature, the Sagas. Etymologically, the word Saga can be traced to its Nordic language origins, having two diacritical dots will render the Swedish word säga meaning to ‘say’ or ‘tell’.

In Scandinavia, Saga is a name of feminine form meaning “she who can see”, blurring the border between fact and fiction even more. Today, Saga refers broadly to a narrative prose, but in narrower definition refers to what was written in Iceland between 1120 and 1400, dealing with themes to do with the families that first settled in Iceland and their descendants. Sagas were also the oral tradition of passing on the histories of the kings of Norway, and with the myths and legends of early Germanic gods and heroes. The myths and stories blend fiction and historical fact in such a way as to keep them interesting and was as such kept alive for hundreds of years in a cultural surrounding where literacy, not to mention pens and paper, were rare or nonexistent, and the written language reduced to what could be chopped into wood with a sword (Old Futhark).

The reason for the similarities in the words Saga, säga and say is that the English language group stems from the northern Indo-European (IE) language family, also called Proto-Germanic, that was originally spoken in approximately the mid-1st millennium BC in Iron Age northern Europe (Baugh & Cable 2003, Barber 1993, Björkman 1978, Geipel 1971, Walshe 1965). Along with all of its descendants it spread with the Germanic peoples moving south from northern Europe in the 2nd century BC, to settle in north-central Europe and from then over to Great Britain, North America, Australia to settle as its most modern and contemporary varieties of New Englishes, where Singlish or Singapore Colloquial English in the Republic of Singapore is but one of them (Wee 1998, Gupta 1994,1992, Kwan-Terry 1978).

Speaking of realities, of reflections of realities that is so mirrored in these waters, I am brought from Carlettí’s 1600s factual observations to Lewis Carroll’s 1800s fiction of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland and Through the Looking Glass. Here’s a tangent story from the point of view of Mary Poppins, P.L. Travers’ magical character from the 1900s, of an afternoon spent in Wonderland with Alice Kingsley, at one of Mad Hatter’s numerous tea-parties. Carroll’s Wonderland being long established in the literature as a place of constant adventure and exploration:

It was another fantastic afternoon tea party put together by the Mad Hatter, thought Mary. She had just gotten to know Alice and was rather new to the crowd but she didn’t mind the company one bit. She was told that they were all mad here, but then again, she had always believed in the element of Fun in anything that needed to be done.

Alice, being of a quizzical person herself, now seemed a little at a loss of her realities, right in mid tea party!

Mary, noting Alice’s distraction and amused at the thought of creating the perfect reality in the everyday mundane, where in her opinion, Alice seemed quite the expert at, turned to Alice and offered in comfort:

“You know dear, there are worlds beyond worlds and times beyond times, all of them true, all of them real, as children understand.”

“Yes you need to believe in things that aren’t true. How else can they become?” said the Dormouse absent mindedly, half dosing at this tea party as when at any other.

Alice laughed. “There’s no use trying,” she said “one can’t believe impossible things.”

“I daresay you haven’t had much practice,” said the White Queen who sat endlessly fixing her shawl, next to the Dormouse. “When I was your age, I always did it for half-an-hour a day. Why, sometimes I’ve believed as many as six impossible things before breakfast. There goes the shawl again!”

“But if you are going to make happen what you believe, perhaps you should be more specific about the details?” chimed the Cheshire Cat, suddenly appearing from out of nowhere, as usual.

Alice was by now not just distracted but completely perplexed, “What details ought I be more specific about?”

“Well it depends a good deal on what you want to make happen.” said the Cheshire Cat, grinning.

Alice didn’t know what about or why the Cheshire Cat was grinning. She simply assumed that’s what Cheshire Cats do, even when invisible.

“I don’t care much what details of reality, so long as I have it.” said Alice verily.

It was at this time that the Hatter, having done his rounds at the party, plunked himself right next to Alice in mid-conversation:

“But of course you do! Remember that time, right after falling down the rabbit hole? You had this silly obsession about Saunas! And then remember what happened after? For Frabjous sake Alice, we were all in the Tropics. And there’s nothing romantic about being in a Sauna, on a breezeless night, in the Tropics! We could all have diffocated trying to teach Dormouse and Mock Turtle the futterwacker, preventing in a whisker, Mock Turtle being turned into a Soup!”

Alice fell silent for a moment, having not a clue what the Hatter was on about. But she was so very fond of him and his galumphing madness that she gave what he said a thought. Besides, the best people often are off their heads, as such, incapable of getting lost.

“Well, I always did prefer the Rain” said Alice.

“That’s right Alice, if you are going to make happen a dream – details – you’ll need to pay attention to the details!” quipped the Dormouse, who awoke then promptly fell asleep again as a cushion into its teacup.

Mary smiled in Alice’s direction with knowing in her eyes. There were so many supercalifragilistic details of realities to share with Alice Kingsley. And Alice was certainly here to stay in Wonderland, thought Mary. All that’s needed is for Alice to come around to that idea herself.

Family history, stories of travels both fact and fiction, remind me of what American writer Carson McCullers once wrote:

“We are torn between a nostalgia for the familiar and an urge for the foreign and strange. As often as not, we are homesick most for the places we have never known.”

Considering the Cordeiro genealogy, my own island hopping and continued interest in global trade in one form of another, where some of my closest friends of today are also wine merchants in the food and beverage industry that – we are homesick most for the places we have never known – now that is a thought to ponder, isn’t it?

References

- Barber, C. 1993. The English Language: A Historical Introduction. (Cambridge Approaches to Linguistics). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Baugh, A.C. and Cable, T. 2003. A History of the English Language. London: Routledge.

- Björkman, E. 1978. Scandinavian Loan-words in Middle English, Scholarly Press, M.I.

- Carlettí, F. 1964. My Voyage Around the World: the Chronicles of a 16th Century Florentine Merchant. Pantheon Books: New York.

- Geipel, J. 1971. The Viking Legacy: the Scandinavian Influence on the English Language. Newton Abbot: David and Charles.

- Gupta A. F. 1992. The pragmatic particles of Singapore Colloquial English. Journal of Pragmatics, 18:31–57.

- Gupta A. F. 1994. The Step-Tongue: Children’s English in Singapore Multilingual Matters, Clevedon.

- Kwan-Terry A. 1978. The meaning and the source of the “la” and the “what” particles in Singapore English, RELC Journal 9(2):22–36.

- Walshe, M. O’C. 1965. Introduction to the Scandinavian Languages. (The Language Library). London: Andre Deutsch.

- Wee L. 1998. The lexicon of Singapore English. In Foley J. et al English in New Cultural Contexts: Reflections from Singapore, Oxford University Press, Singapore, pp 175–200.

- Welsh, J. 2004. Kraak porcelain: the rise of global trade in the late 16th and early 17th centuries. Jorge Welsh Books, UK. Internet resource, at jorgewelsh.com retrieved 22 Feb 2013.