From Castell de Montjuic silent large-calibre guns overlooks the sea and port as well as the metropolis of Barcelona itself. On the west side, stands an ornate memorial to General Francisco Franco. An unintentional but vivid commentary on the history of Spain and Barcelona as good as any history book would offer.

JE Nilsson and CM Cordeiro Nilsson © 2011

The headline pun is, of course a play on the words from the English translation by D. L. Ashliman of the definitive edition of the Grimm’s Kinder- und Hausmärchen (Berlin 1857), tale ‘Snow White’, in which the Queen asks her magical mirror “Mirror, mirror on the wall / Who in the land is fairest of all?” The tale takes a dramatic turn when the mirror tells her an unwanted truth.

In a similar manner, the period around the early 1900’s was extraordinarily volatile when it came to artists and architects communication with the public. Many of the art movements that enriched the early 1900’s in Europe were protests against those in power that for their winnings sake drew the world into war. Various kinds of repression caused new ways of commenting on society to appear.

Outside of The Fundació Joan Miró Museum in Montjuïc, Barcelona, a large sculpture on the grass lawn looks like blades of a huge propeller which however lacking proper organization will work against each other and go nowhere.

There was dada-ism, that was anti-war, anti-bourgeois and anarchist in nature, peaking 1916 to 1922 and laying the foundation for Surrealism that begun in Paris in the early 1920s. The Dada founder André Breton, who had trained in medicine and psychiatry, served himself in a neurological hospital where he used Sigmund Freud’s psychoanalytic methods with soldiers suffering from shell-shock, and was very much aware of the gory realities of war.

Outside of the Fundació Joan Miró Museum in Montjuïc, Barcelona you are met with this soft and large metal object as a more humane counterpoint to the silent large-caliber guns outside the Montjuïc fortress nearby. On its top, it has a large head for reflections, of which its two most significant features are two wide open eyes for observation. On what appears to be the body it has two not very efficient looking legs – Barca would never sign this guy up – and three protrusions for manipulation of its surroundings, of which two are hands.

The following surrealism was considered both philosophical and revolutionary. In this Sigmund Freud’s dream analysis and the unconscious also had its place, since this was of utmost importance to the Surrealists in developing methods to liberate imagination while still staying focused on that there were still a meaning to it all, or as Salvador Dalí explained it: “There is only one difference between a madman and me. I am not mad”.

What was Miró’s art all about then?

A lot indeed happened here in Barcelona. Straight below, in more or less the direction in which the gun points, is the old city district Barri Gothic where Joan Miró (1893-1983), Spanish painter, sculptor and ceramist grew up. He worked and studied here and faked a nervous breakdown while threatened with being forced into business work instead of becoming an artist. In the 1920s he moved to Paris where he got in contact with the Surrealist movement, and after the Civil war in Spain in the 1930s and WWII, he developed his art to a mostly linear and very clear cut symbolism, that for nearly seven decades has intrigued and enchanted art lovers worldwide until his death in 1983. He’s even buried here on Montjuïc.

Miró’s revolution was as I see it on the personal plane. As I understand what I have seen of his work, his interest was women, and the ever present discourse between the genders, where he endlessly sought a way of expressing this that could go on reasonably undetected by the repressive forces at hand. While I find it hard to say if they actually pushed the development towards a different society they certainly reflected the change.

In many ways Miró followed the same route as Picasso, both with their roots in Barcelona they developed their art in Paris. Both were influenced by the interest that the Surrealists took in Freud and his studies of the unconscious reflections of as the mind’s dark side, deep fears, inexpressible longings and the most basic drives.

The Surrealists cherished this as they scorned rationality and technology and all the other values of the previous generation that had led to the horror of the World War I, placing their faith instead in the alternate reality of chance, desire, coincidence and dreams.

Even if Miró is still seen as one of the founders of Surrealism, he did not feel he belonged to them.

By the time I arrived at an understanding of Surrealism, the school was already established. I was swept along by André Masson, Max Jacob, and I followed them, but not everywhere they went. They form a battalion, a company if you like, and everything they do is strictly disciplined. I want to be independent. … But art doesn’t exist for the Surrealists. What they understand by art is anti-art.

A very lonely figure overlooks his birth place, the Barri Gothic in Barcelona, from the roof top of the Miró Museum on Montjuïc

After 1940 Miró’s paintings started to focus on symbols as what appears to be synthesized curves. As we are able to recognize a particular fruit from a small part of its curved surface, one could think that Miró simplified what appears to be human lines into its most basic shorthand pictures. The paintings are often described to depict birds – that can fly in the sky, stars – that are unreachable, and women.

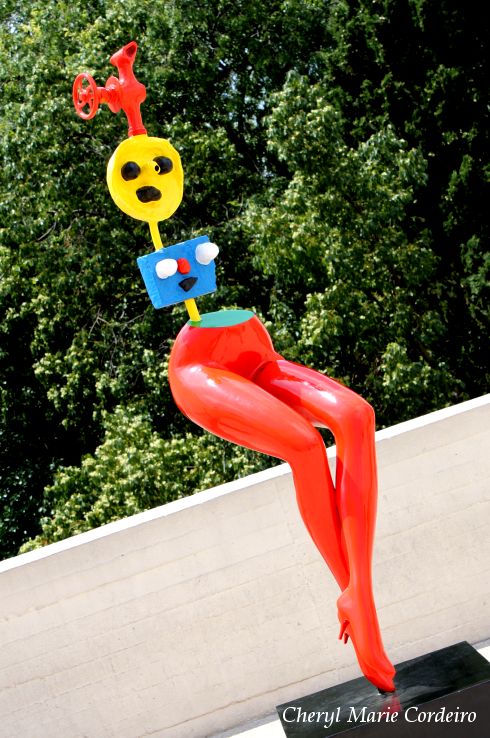

A female looking figure in primary colors. Detail. The blue thing on top is usually described as a bird, maybe with a “star” on top, both signified as being unreachable.

A small figure made from a stool with its legs outstretched towards a figure with female legs in the far distance of the roof of the museum. On the apparent head of the figure a Spanish matador’s hat. Attached to one of the legs of the stool, a yellow dumbbell. Through the two empty holes in the blue head looking tin, you can see all the way to a figure on the other side of the roof with stunningly red and curvy legs.

The distant figure with the red legs. Mid section with a blue face looking section, as in one person inside the figure, and on top a second yellow face crowned by a tap, a utility which function is to facilitate the ‘turning on and off’, at will.

In 1931, in the course of an interview with Francisco Melgar in Ahorn (Madrid), Miró spoke out even more vehemently on his work.

Rules? Art defies them… I personally don’t know where we are heading. The only thing that’s clear to me is that I intend to destroy, destroy everything that exists in painting. I have an utter contempt for painting. The only thing that interests me is the spirit itself, and I only use the customary artist’s tools—brushes, canvas, paints—in order to get the best effects. The only reason I abide by the rules of pictorial art is because they’re essential for expressing what I feel, just as grammar is essential for expressing yourself.

Now, I’ll just add one more picture and leave the interpretation up to you. This is from Wikipedia, the sculpture is called “Dona i Ocell” or “Woman and Bird”, 1982, Barcelona, Spain.

“Dona i Ocell” or “Woman and Bird”, 1982, Barcelona, Spain

– – – o o o O o o o – – –

Interesting reading: Joan Miró: Selected Writings and Interviews, edited by Margit Rowell. Translations from the French by Paul Auster. Translations from the Spanish and Catalan by Patricia Mathews. G.K. Hall and Company, 326 pages, 1986.

Miró: Driven by abstraction but tied to the Catalan soil by Roderick Conway Morris, New York Times.

One thought on “Miró, Miró on the wall …”