East to west bound, Sweden.

Text & Photo © JE Nilsson, CM Cordeiro, Sweden 2016

“The first aspect of systems thinking concerns the relationship between the part and the whole. In the mechanistic, classical scientific paradigm it was believed that in any complex system the dynamics of the whole could be understood from the properties of the parts. Once you knew the parts, ie their fundamental properties and the mechanisms through which they interacted, you could derive, at least in principle, the dynamics of the whole. Therefore, the rule was: in order to understand any complex system, you break it up into its pieces. The pieces cannot be explained any further, except by splitting them into smaller pieces, but as far as you want to go in this procedure, you will at some stage end up with fundamental building blocks- elements, substances, particles, etc- with properties that you can no longer explain. From these fundamental building blocks with their fundamental laws of interaction you would then build up the larger whole and try to explain its dynamics in terms of the properties of its parts. This started with Democritus in ancient Greece and was the procedure formalized by Descartes and Newton, and has been the accepted scientific view until the 20th century.

In the new paradigm, the relationship between the part and the whole is just the opposite. We believe that the properties of the parts can only be understood through the dynamics of the whole. The whole is primary, and once you understand the dynamics ofthe whole, you can then derive, at least in principle, the properties and interactions of the parts. This reversal of the relationship between the part and the whole occurred in science first in physics during the first three decades of the century, when quantum theory was developed. In those years, physicists found to their great amazement that they could no longer use the notion of a part – such as an atom, or a particle – in the classical sense. Parts could no longer be well defined. They would show different properties, depending on the experimental context, appearing, for example, sometimes as particles and at other times, as waves.

Gradually, physicists began to realize that nature, at the atomic level, does not appear as a mechanical universe composed of fundamental building blocks but rather as a network of relations, and that, ultimately, there are no parts at all in this interconnected web. Whatever we call a part is merely a pattern that has some stability and therefore captures our attention. Werner Heisenberg, one of the founders of quantum theory, was so impressed by the new relationship between the part and the whole that he used it as the title for his autobiography Der Tedl und das Ganze.” [1:475]

Train home

She stepped into the the train station with only a black backpack on her. The routine sweep of her eyes around the train station rested first on the large analog clock. It was a familiar sight, an object of linear Time that sat on the left wall located next to the entrance of a plush corner café in which had so many times before, ordered a caffè macchiato, just fifteen minutes before the train departed from this city to the next, southbound.

Ten minutes to train departure. She decided this time, to step left of linear Time into the small convenience store to browse its shelves. At least twelve assorted types of dairy products with various cultures sat before her on the shelves ready for harvest, and she caught herself thinking, “Ah. Home.” Seeing through the numerous colourful packagings of yoghurts, product differentiated yet ubiquitous, it was as much here as any other train station, any other grocery store, she grabbed one. Her favourite. It said on the bottle, 4% sugar.

If there were any thoughts at the train station, she had none to voice. It was rather a feeling of the place, that everywhere was distinct yet the same and she could as much feel at home in one place as another, all because of this 4% sugar label.

Platform 5, and two minutes before departure, the train pulls in. Was it Vagn 6 that was usually detached at some point in the line and people had to switch carriages? She figured someone would inform her if that were the case. She boarded Vagn 6.

As the train pulled away from the platform gaining speed, the startup of the engines soon became a quiet droning. Sometimes it was the case that the low hum of the machine at full speed lullabied her to sleep. But this day, it was different, so-and-so. With chin resting in her upturned palm and elbow on the window sill of the train, she peered out unto the semblance of Tolkein’s Midgard. From a distance, from a speed, it was picturesque beautiful. And because you couldn’t reach out and touch it as such, it was at the same time, a void. A void that she noticed many would try to sidestep in their daily lives, almost afraid to encounter it. One always had something else to do than to stare into this void. But it was the very nature of this void, that had come to fascinate her of late, what made part of her train of thoughts.

“So spacetime not only can be curved, can be shaped, it’s also full of life so to say. It is really physical material that you can study. And if you take a chunk of this quantum spacetime, because of all this phenomena, there’s energy in it. And this energy because of quantum theory, that’s this dark energy, that’s the phenomena that cosmologists measure. So I like to joke that empty space, that vacuum is the most fascinating thing to study in physics, of course writing big grant proposals to study nothing might actually not come across very clear, but in effect that’s what we’re doing…” [3, 26:43-27:15]

She lowered her elbow from the window sill of the train, taking her palm rest from her chin. Her eyes continued to follow the lines of the the landscape of Midgard.

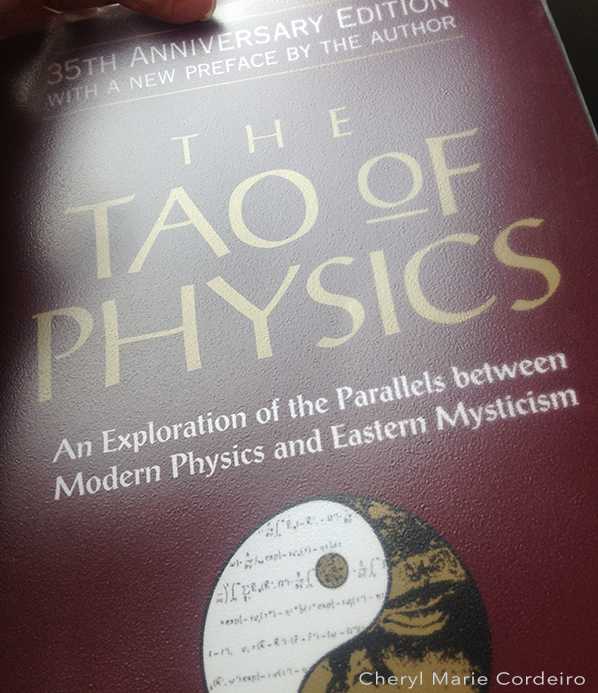

Fritjof Capra is also author of Tao of Physics published first in 1976 [2]

Reference

[1] Capra, F. (1985). Criteria of systems thinking. Futures, 17(5), 475-478. doi:10.1016/0016-3287(85)90059-X

[2] Capra, F. (1976). The Tao of Physics: An exploration of the parallels between modern physics and eastern mysticism. London: Fontana/Collins.

[3] Dijkgraaf, R. (2012). The End of Space and Time? Lecture at Gresham College, internet resource at https://youtu.be/XDAJinQL2c0. Retrieved 26 April 2016.