The facade of Ruínas de São Paulo or the Ruins of St. Paul’s, Macau’s historic landmark that attests their Portuguese heritage.

Photo © C M Cordeiro-Nilsson for CMC 2010

In today’s modern Macau, it is difficult to find any trace that Macau had set out its life as a western outpost in Asia, as a matter of fact together with Malacca as one of the oldest. Macau is also one of the most visible reminders of the fact that it was actually the Portuguese explorer Bartholomew Diaz who in 1488 discovered a sea route to China and that Great Britain, still so present in today’s Singapore, arrived centuries later in the Far East.

Today Macau has been given back to Chinese administration, however the remnants of Portuguese culture is deeply instilled in the food, culture and architecture of Macau. During my recent visit, one of my ‘most important places of interest’ was the Ruins of St. Paul’s Cathedral. To find my way there was a mixed experience.

The Ruins of St. Paul is constantly filled with people, so walking from Senate Square in the direction of the Macao Museum would be one of the most convenient means of getting there. Even when driving, we parked some 400m away and walked.

Parking meters is the system in Macau when parking along the streets.

Scooters, a common sight and mode of transport.

All the better to navigate these older, narrow streets.

Parking meters are the system in Macau, if you’re driving and you’ll also notice a fair bit of scooters and small motorcycles on the roads, which are excellent vehicles to navigate the narrower streets of the region.

The Ruins of St. Paul is today what is left of a Portuguese Jesuit cathedral that was accidentally destroyed by fire in the early 1800s. Dedicated to Saint Paul the Apostle, it was in the 1600s, a collegiate church that the Jesuits used to house those of their society who were on their way to Japan, via Macau. These ruins are one of the region’s most historic landmarks and enlisted as part of UNESCO’s World Heritage Site in 2005.

The back of the facade to the Ruins of St. Paul where extensive renovation was carried out that straightened the facade, correcting its dangerous lean.

In this post, you’ll find a brief description of the Ruins of St. Paul from a book by Anders Ljungstedt (1992:14ff), republished from the Chinese Repository.

Anders Ljungstedt (1759-1835) was born in Linköping, Sweden where in 1798, he arrived on a Swedish East Indiaman at Canton and stayed on as a resident supercargo. After the closing of the Swedish East India Company in 1813, he moved to Macau where he remained till his death in 1835. He spent the last twenty years of his life devoted to the study of the history of Macau. His study was first published in 1832 (revised and published again in 1836) and is acknowledged as having been the first scientific historical study of Macau.

He was a Swedish Knight of Wasa, a scholar and a philanthropist. Though he never returned to Sweden, in 1824, he donated a large sum of money for a school to be built in Linköping, Sweden, where it still stands today.

In classic Chinese blue and white, Calçada de S. Paulo.

Just across from the ruins is the Macao Museum and Monte Fortress.

The following description of the collegiate church of St. Paul is from Ljungstedt’s description of the Divisions of Macao

1. Parochial Districts. A concise description of the principal PUBLIC BUILDNGS must convince us, that the ancient inhabitants spared neither treasure nor pains to embellish and protect Macao. Churches. The districts borrow their names from their respective Parish churches. The cathedral, dedicated to St. Peter, gives to the principal district the denomination of Bairo da Sé. When this church was raised I do not know. The second an dmost extensive district is called Bairo de St. Lourenco, from St. Lawrence, its patron. To judge from an inscription, this temple may have been rebuilt in 1618. The third and most limited district is the Bairo de St. Antonio, from the church of St. Anthony, it was burnt in 1809, and rebuilt by liberal contributions of both Roman Catholics and non-romanists.

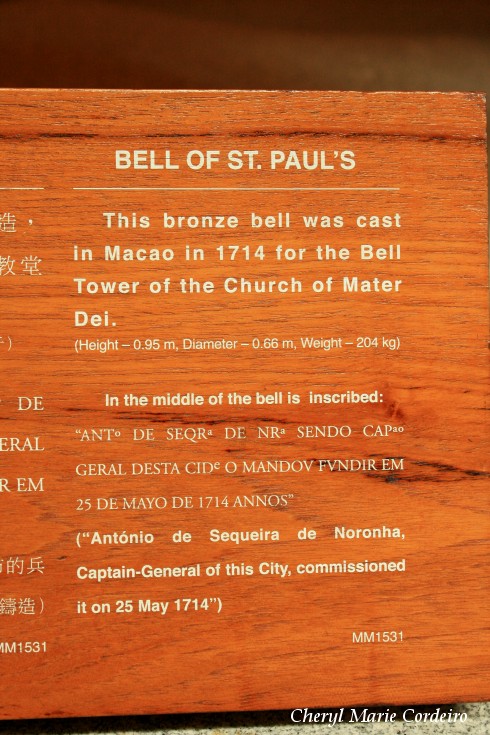

Bell of St. Paul stsands exhibited at the museum.

Text to Bell of St. Paul.

Collegiate Churches. St. Paul. By a private manuscript we are informed that Francis Peres and a few Jesuits had (1565) a house where they used to lodge those of their society, who went by way of Macao to Japan. A church was coeval with their entrance in China, it was burnt by accident. The noble building commonly designated by the name of St. Paul, “St. Paolo”, was erected in 1602 as expressed by VIRGINI MAGNAE MATRI, CIVITAS MACAENSIS LUBENS, POSUIT AN. 1662. (sic – should be 1602, ed) an inscription engraved on a stone fixed in the western corner of the edifice.

The old church was consecrated to our Lady, the mother of god “nossa Senhora da madre de Deos” and so is the modern. The frontispiece, all of granite, is particularly beautiful. The ingenious artist has contrived to enliven Grecian architecture by devotional objects. In the middle of the ten pillars of Ionic order, are three doors, leading to the temple; then range ten pillars of Corinthian order, which constitute five separate niches. In the middle one, above the principal door, we perceive a female figure, trampling on the globe, the emblem of human patriotism, and underneath we read MATER DEI. On each side of the Queen of Heaven, in distinct places, are four statues of Jesuit saints. In the superior division, St. Paul is represented, and also a Dove, the emblem of the Holy Ghost. In this edifice is a clock, which strikes quarters and hours, and to judge from an inscription on the principal wheel, Louis XIV, made a present of it to the Jesuit college.

Just a few steps up from the Ruins of St. Paul is the Monte Forte or the Fortress of Our Lady. As a symbolic thought about how often the westerners have come to new regions of the earth with the bible in one hand and the sword in the other, this fort makes up an important part of the historic center of Macau and was built during the 1600s – by the Jesuits.

On the contrary, it is Macau’s glitz and casinos, one of which is the Grand Lisboa, that lends the region its success.

I was mostly taken in by the canons that lined the garden walls, reminding me most of all of the armament of the Swedish East Indiaman Gotheborg.

Besides these reflections this is a completely serene place at which to spend an afternoon, if the sun isn’t blazingly warm on that day, the rooftop garden itself offering a splendid view of the city.