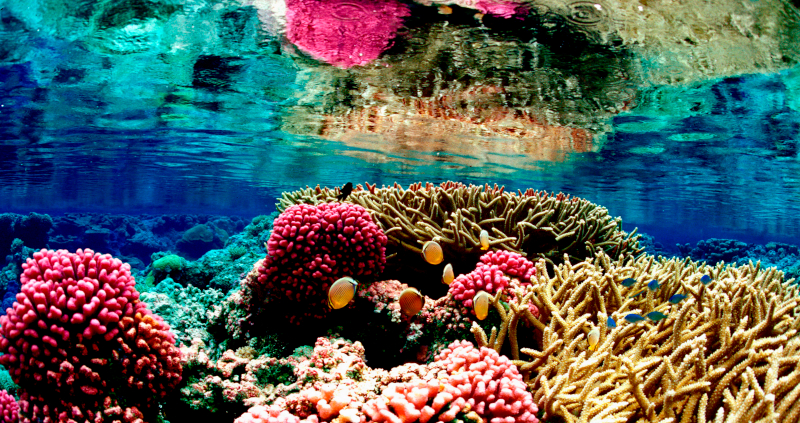

Coral reef ecosystem at Palmyra Atoll National Wildlife Refuge.

Photo credit: Jim Maragos / U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service

In a conversation with Steven Bartlett on The Diary of a CEO (aired August 29, 2024), neuroscientist Andrew Huberman revisits one of his earliest fascinations: aquaria. From childhood, he immersed himself in the study of tropical fish and coral reef ecosystems — enclosed microcosms of life that pulsed with interdependence, fragility, and pattern.

Over time, what began as a child’s biological curiosity matured into a worldview — one that understands society, emotion, and healing through the lens of systems. To see life as an aquarium — or a coral reef — is to acknowledge that what holds things together is often unseen. Coral ecosystems do not privilege visibility; they rely on relationships, flows, and functions. Tiny filtering organisms maintain balance. Root-like structures anchor the entire reef. Each component has significance — not in isolation, but in relation to others.

This is the essence of systems thinking: a departure from linear cause-and-effect models toward an understanding of wholes, feedback loops, emergence, and interconnection.

Coral Reefs as Systems

A coral reef is not simply a collection of organisms. It is a living system — dynamic, adaptive, and composed of multiple nested subsystems. Reef fish, crustaceans, anemones, and algae interact in a co-regulated rhythm. Change in one part of the system creates ripples throughout.

Huberman’s metaphor of the “aquarium of life” aligns with this ecological reality. The reef is not held together by a central authority, but by the quiet interdependence of its members. Likewise, human systems — from friendships to institutions — function not through dominance or visibility alone, but through countless unspoken acts of balance, repair, and quiet contribution.

Emotional Ecology and the Structure of Support

In the podcast, Huberman reflects on a particularly difficult moment in his life — a time when internal order gave way to emotional chaos. In that silence, a friend appeared: Lex Fridman, who showed up without advice or commentary, simply to sit beside him.

From a systems perspective, this moment isn’t incidental. It represents homeostasis — a system’s effort to stabilize itself through feedback and presence. Lex didn’t solve a problem. He became part of the regulatory mechanism. Like a stabilizing species in a reef, he modulated the flow — an emotional buffer, quiet and essential.

In ecosystems, this kind of buffering is often performed by unassuming organisms. Sponges filter toxins. Mangroves slow water flow. These functions are rarely glamorous, but they are structural. Support, too, can be structural — not performative, not loud, but quietly ecological.

Fragility and Resilience in Complex Systems

Coral reefs are both stunning and vulnerable. They can collapse from subtle shifts in temperature or pH, and yet, under the right conditions, they regenerate. Human lives — particularly those shaped by trauma, emotional volatility, or high-functioning stress — often mirror this balance of fragility and resilience.

Huberman’s narrative traces that arc: from instability in youth to disciplined recovery through therapy, community, and biology. Beneath the neuroscience lies a deeper insight: resilience is not a solo achievement. It is systemically enabled. It depends on context, environment, and others — sometimes seen, sometimes unseen.

This reframes healing not as an individual act, but as a networked reconfiguration — a rebalancing of flows, supports, and inner ecology.

Seeing Systems Where Others See Individuals

To adopt a systems mindset is to look beyond the individual organism and observe the architecture of interaction — the dependencies, the flows of energy, the emergence of properties not visible from any single part.

What I find fascinating about systems thinking is how it mirrors the way life feels beneath the surface. Linear cause-and-effect models always seemed too neat, too mechanical — as if a single action could explain the complexity of experience. But the idea of feedback loops, emergence, and interconnection makes more sense to me. It allows for nuance, for quiet influence, for unseen roles to matter. It helps explain why something small can shift everything, or why presence — not performance — can stabilize a person. In systems thinking, there’s space for softness, for ambiguity, for patterns that unfold over time. It’s not a tool for solving life, but for seeing it more clearly.

The coral reef metaphor does not simplify life. It complexifies it. It invites an ecological view of experience — one in which personal crises are not anomalies, but symptoms of systemic imbalance. One in which support can be as simple — and as vital — as being present.

While the episode with Andrew Huberman travels through familiar terrain — neuroscience, mental health, personal growth — it gestures toward something quieter and more spacious: a way of seeing life not as a ladder to climb, but as an environment to inhabit with care.

Not every presence needs to speak.

Not every function needs to be seen.

And yet, in systems — as in coral reefs — everything is connected.