Photo & Text © 2025 JE Nilsson, CM Cordeiro

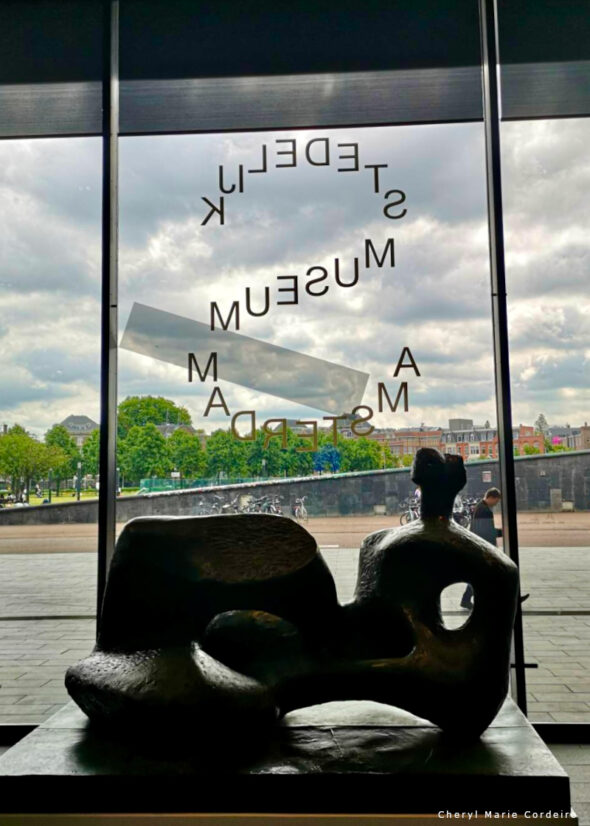

This past week I visited the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam, a space where the 20th and 21st centuries collide in forms that are sometimes luminous, sometimes reverent, often dissonant, and occasionally maddeningly ambiguous. It’s not a museum that asks for your agreement. But it does demand your attention.

A Walk Through Time and Form

The Stedelijk is known for its impressive collection of modern and contemporary art and design. That reputation becomes immediately clear, not through spectacle, but through a thoughtful, often intimate curation. The collection moves fluidly between movements: De Stijl, Bauhaus, Abstract Expressionism, Minimalism, and into the chaotic openness of contemporary installation and conceptual art.

I’ve always had a soft spot for abstract work. When I visited Barcelona in 2011, I spent time in both the Fundació Miró and MACBA. They were two very different experiences, but each left a mark. I remember standing in front of pieces by Joan Miró, wondering: Is this abstract? Surrealist? Both? His playful forms and symbols seem to slip between categories, refusing easy labels.

That same intrigue resurfaced last week at the Stedelijk. There, I found myself lingering in front of a piece by Marlow Moss. Crisp, calculated lines laid down with such rhythmic precision they almost felt like a spiritual exercise. Moss, a lesser-known contemporary of Piet Mondrian, brings a clarity to geometric abstraction that feels both intellectual and strangely devotional. Her work doesn’t shout; it’s disciplined. Like a measured breath, or a line that knows exactly where to stop.

A few rooms later, Mark Rothko’s Untitled (Umber, Blue, Umber, Brown) quietly pulled me in. I’ve always loved Rothko, nearly all of his works. If I could place one of his moody meditations next to a Lucio Fontana canvas in my living room, that might just be heaven. This particular piece didn’t just sit on the wall. It pulsed. Rothko never paints just color; he paints feeling. Grief, dignity, solitude, all wrapped into dense, bleeding rectangles of color. It’s not a performance. It’s a presence.

The Present as Provocation

And then came the plastic bottles.

An installation by Pamela Rosenkranz, featuring rows of collected bottles filled with unnaturally colored liquids. Discarded packaging turned into an art object. It’s meant to explore themes of consumption, perception, and artificial purity. And while some might find that rich with conceptual meaning, I felt more ambivalent. I think I drank one of those neon-colored liquids bought off the shelves of the grocery store located across from the museum just prior to entering. Seeing it now, lined up like a laboratory of synthetic toxins, made me second-guess my hydration choices.

Is this art? A critique? Or is it simply a provocation dressed as reflection? Maybe both. Rosenkranz certainly evokes questions, about health, capitalism, human bodies, and plastic waste, even if those questions remain unresolved. If the goal was to spark discomfort or contemplation, it succeeded.

On Collection and Contradiction

What stands out about the Stedelijk’s collection isn’t just the timeline or variety of media, rather, it’s the museum’s philosophical elasticity. You’re not just moving through galleries. You’re moving through evolving vocabularies of meaning. From the structured utopias of early modernism to the fragmented, self-aware gestures of today’s artists, the museum doesn’t present a linear story. It stages a conversation and sometimes even an argument between works.

Importantly, it also gives space to female artists, queer perspectives, and voices outside the Western canon. It challenges easy narratives and tidy categories. And yet, that tension between provocation and profundity can sometimes feel precarious. Not every piece lands. Some teeter on the edge of self-parody. But that friction is part of the experience.

The Stedelijk isn’t about pleasing the eye. It’s about pressing on the mind. Its collection holds a tension between modernity’s dream of clarity and our current suspicion of meaning itself. That’s its strength. That’s also its risk.

If you’re in Amsterdam and looking for more than beautiful objects, if you want a glimpse into how Western art has contorted, reflected, and questioned itself, I think the Stedelijk delivers. Whether you leave with admiration or exasperation, you’ll leave thinking. And in a time when so much is designed to slide past us, thoughtlessly, that might just be the most radical thing of all.