The choir of Saint-Denis, the birth place of Gothic architecture.

Text & Photo © JE Nilsson, CM Cordeiro, Sweden 2016

It is generally thought that Gothic architecture was born when Abbot Suger (c.1081–1151) of the French Royal Abbey of Saint-Denis just north of Paris, undertook the renovation of the then Romanesque style structure of the Saint-Denis, the most sacred shrine in France. The work began in 1140 with the erection of a new western facade, and continued with a new choir at the eastern end, covering as he put it, the alpha and the omega, the beginning and the end of the basilica. Time did not let him see the new nave erected as he planned it but the foundation was laid. As the Saint-Denis Basilica Chatedral stands today what remains of Sugers work is the general appearance of the western fascade minus the northern tower, and the very important new choir at the eastern end. The nave is as he envisioned it but was built after his time. Most of the important glass windows was lost over the years or destroyed at the time of the French revolution at the end of the 18th century.

Suger and the Basilique Saint-Denis

Abbot Suger (c. 1081–1151), was highly educated, having grown up in the abbey and studied at the same school as the future king Louis VI of France. Suger became abbot of St-Denis in 1122 and came to devote his life to the idea of bringing in light into the old church building that he found in a bad state of repair. There are no documents that clearly proves who were the architects of the new buildings but the idea was new as he comissioned it, and thus he brought to life something that became a new style of architecture [1] by visually dissolving the walls and replacing them with huge glass windows, while placing a set of vertical supports (buttresses) on the outside. And if rainbows, nature’s own prism of colours made by an interplay of sunlight through drops of rain could invoke the feeling of sheer joy and wonder in people, then what would make happy, tired people after a day of toil? To that understanding, Suger put extensive efforts into stained glass art to prism the interiors of the church, his passion for the project seemed without bounds:

“The windows were quite certainly Suger’s own distinctive contribution. There must have been at least thirty of them in the choir and the west front. They were his pride and joy. He appointed a special ministerialis magistrum to look after them in the first place. These had to be recruited from ‘many regions’ which suggests that the scale of operations was exceptional and beyond the immediate resources of any one region. This ‘scouring the land’ in search of talent allows Suger to present himself in his favourite role as indefatigable provider. There were other occasions. If necessary he was prepared to fetch marble columns all the way from Rome to match those of the old nave, although in the end he found what he wanted (miraculously of course) in the neighbourhood of Pontoise; and when everyone else had despaired of finding timbers of the right size, he plunged hopefully into the forest of Yvelines, and against the odds, solved he the problem in a matter of hours.” [2:10]

Dionysius the Areopagite and Pseudo-Dionysius

On the ideological level Sugar based his ideas not only on the more direct heavenly authorities like Christ and the patron saints, but also on the mystical writing by Pseudo-Dionysius (probably a 5th-6th century theological philosopher and mysticist from Syria), who from the 9th century had been suggested being one and the same person as the allegedly first bishop of Paris, Dionysius the Areopagite, who had been converted by Saint Paul himself and sent to Paris to convert the people to Christianity, martyred c.250BC, and who then became the patron saint of France.

Translating the metaphysical

Weather these two persons were one and the same is still debated but, while the St Dionysius of France is historically confirmed and buried under the Saint Denis Basilica, he has not left us any of his thoughts in writing which, however, the possibly later 5th century Pseudo-Dionysius, did. It is difficult to conceive that Suger would not be influenced by the literary works ascribed to the very patron saint of his abbey, and likewise available in the church’s own library. As abbot of the Basilique Saint-Denis and a highly educated scholastic statesman, he would most likely been very familiar with the written works collectively known as the Corpus Areopagiticum or Corpus Dionysiacum that comprise four treaties and ten letters and was part of the library collection of the Basilique Saint-Denis [4].

The ideas are to this day reflected even in the sculptural works of Auguste Rodin exhibited in Paris [3] likewise in New York.

And it was that Pseudo-Denys wrote in Mystical Theology chapter I on understanding and translating the metaphysical:

“These things thou must not disclose to any of the uninitiated, by whom I mean those who cling to the objects of human thought, and imagine there is no super-essential reality beyond; and fancy that they know by human understanding Him that has made Darkness His secret place. And, if the Divine Initiation is beyond such men as these, what can be said of others yet more incapable thereof, who describe the Transcendent Cause of all things by qualities drawn from the lowest order of being, while they deny that it is in any way superior to the various ungodly delusions which they fondly invent in ignorance of this truth? [5-7]

If pearls of wisdom of the martyred Saint of that church was non-disclosure, what other means could Suger be driven to illustrate the Divine but by bringing Nature into and within the walls of the church?

This translation of ideas from the metaphysical contemplations of Pseudo-Denys to Suger’s Basilique Saint-Denis came in the form of most notably the stained glass windows that brought in light (Light) into the church’s interiors, as symbol to the way to True Light and an understanding of what laid beyond one’s physical senses that filtered and showed only the material. Even to Suger, Christ was a figure, a symbol of an enlightened being, for which to move past in order to see True Light:

“xxvii. Of the cast and gilded doors.

Whoever thou art, if thou seekest to extol the glory of these doors, marvel not at the gold and the expense but at the craftsmanship of the work. Bright is the noble work; but, being nobly bright, the work should brighten the minds, so that they may travel, through the true lights, to the True Light where Christ is the true door. In what manner it be inherent in this world the golden door defines: the dull mind rises in truth through that which is material, and, in seeing this light, is resurrected from its former submersion.” [1:5]

Knowledge asymmetry

“The world which Dionysius understands God to have created is one which encompasses many forms of being. The lowest such form is that of lifeless material beings (e.g. stones and rocks), whilst the highest is that of the angels, who were immaterial, intellectual (νοερός) and rational (λογικός) beings. Between these are found further levels of being. Above the level of lifeless beings are the forms of living beings which lack intellect or reason, namely the plants and animals, whilst beneath the level of being of the angels is the level of being of men, who are composed of both material bodies (akin to the animals) and of immaterial souls (akin to the angels)” [4:227]

Human psychology and consciousness today

However phrased, it is understood that nature has levels of existences that when viewed in relation to each other, encompassed asymmetric developmental stages. Today, in terms of the development of human cognition, the differentiation in levels of human development for each individual or groups continue to be the very study of human psychology and consciousness today, where scholars such Abraham Maslow, Jane Loevinger, Clare Graves, Lawrence Kohlberg and Ken Wilber [8] are some who have put forth theories and models in the field towards a better understanding of human and social behaviour.

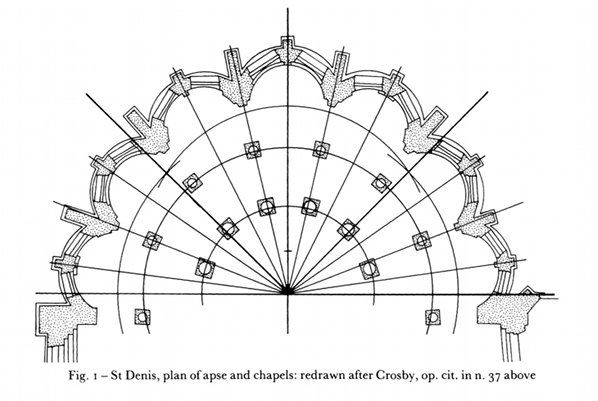

Suger’s remarkable contribution was how he translated this asymmetry of knowledge, written as non-disclosure in Pseudo-Denys’ works, into the very architecture of the church. The diagram from Kidson redrawn after Crosby [2:12] shows that the apse of St Denis was not even a simple matter of one concentric circle. There were two centres, and two radii, with the chapels themselves forming a series of subordinate circles. Moreover there is asymmetry in the eastern arc, having a shorter radius and a different centre, 2.70 m to the east of the principal centre. This broke away from the tradition of concentricity and the symmetry of the vault in Romanesque architecture.

This illustration of the asymmetry of knowledge and different levels of existences, Gothic architecture is characteristically elliptical and could be said to suggest heliocentricity in its perspective, compared to the previous era of Romaneque constructs.

It is also to say that encompassed with True Light is Darkness in itself, of which little can be known for those who stand only in Light.

Congruent management of asymmetry

This asymmetry in knowledge so encompassed by the human being’s physicalities, could be thought to have its various manifestations at different socio-political levels. The building of such early churches known to be the time’s skyscrapers and pinnacle of technological and engineering knowledge. The price to pay for the quest of absolute acquisition of such knowledge has left its traces throughout history from the time of the Crusades until today.

In his time, Suger sought to compare the glory of the treasures of Hagia Sohia in Constantinople Istanbul, to the beauty of Basilique Saint-Denis. In common between the Hagia Sophia and the Basilique Saint-Denis is the shifting symbolisms of what is through time.

Meaning is arbitrary, the symbols of the mind shapeshift through time. The elliptical and asymmetrical constructs of the Basilique Saint-Denis that signifies the ‘Gothic’ architecture illustrates the Divine, and in so doing also illustrates the short-comings of the human mind.

Diagram from Kidson redrawn after Crosby showing that the apse of St Denis was not a simple matter of concentric circles [2:12].

From the end of the 13th century and early 14th century new chapels were erected between the buttresses along the north aisle of the nave making the Basilica look much wider on the outside.

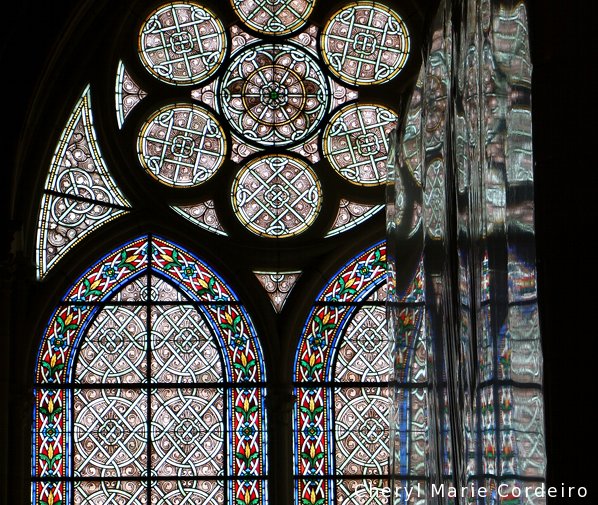

Rose window of the north transept of the Basilica.

The north transept stained glass rose window features the Tree of Jesse.

Dessert as lunch: a labelled ‘soft chocolate cake’ that is what others might have labelled a ‘molten lava chocolate cake’. The concoction by whatever name, served with a side of sweetened whipped cream, was luscious.

References

[1]Frisch, T. G. (1987). Abbot Suger of Saint Denis: The Patron of the Arts. In: Gothic Art 1140- c.1450: Sources and Documents, Teresa G. Frisch (ed.), reprinted 2004/1997. University of Toronto Press and The Medieval Academy of America: Toronto, Buffalo, London, pp. 4-10.

[2] Kidson, P. (1987). Panofsky, suger and st denis. Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes, 50, 1-17.

[3] Cordeiro, C. M. (2016). The latent image, Cheryl Marie Cordeiro, internet resource at http://www.cherylmariecordeiro.com/?p=33250. Retrieved 28 March 2016.

[4] Brown, A. (2012). Dionysius the Areopagite. In: The orthodox christian world Augustine Casiday (ed). Abingdon: Routledge, pp 226-236.

[5] Stanford University (2014), Pseudo-Dionysius the Areopagite, First published Mon Sep 6, 2004; substantive revision Wed Dec 31, 2014. “Ch. 1: Introduction, and allegory of Moses’ ascent up Mt. Sinai.” Internet resource at http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/pseudo-dionysius-areopagite/#MysThe, retrieved 27 March 2016.

[6] Pseudo-Dionysius Areopagita. Uber die mystische Theologie und Briefe, Stuttgart: Hiersemann (1994). Translation, internet resource at Prof. Dr. William J. Hoye, http://www.hoye.de/theo/denistxt.pdf, retrieved 27 March 2016.

[7] Rolt, C.E. (2000). Dionysius the Areopagite: On the Divine Names and the Mystical Theology. Internet resource at http://bit.ly/1SowRZV, retrieved 27 March 2016.

[8] Wilber, K. (1980). The atman project: A transpersonal view of human development. Wheaton, Ill: Theosophical Pub.House.